Running a public authority in Punjab that operates across the province to open doors for young people with new and innovative ideas is an exciting challenge. The goal is to provide these individuals with space to bring their creativity to the public—a concept similar to an open incubation center.

However, a significant issue has emerged. Most visitors to our center are not innovators; they are simply job seekers. Many come with degrees and impressive grades but lack the practical skills needed to create something new or to meet market demands.

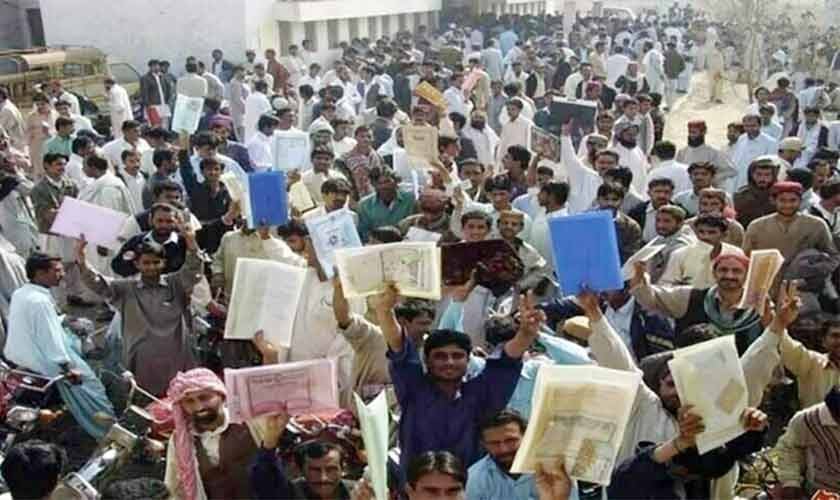

Every year, Pakistan’s universities celebrate their graduates, awarding nearly 800,000 degrees. Families proudly place garlands around the graduates’ necks, and hopes for a bright future fill the air. Yet, for many young men and women, this joy is short-lived. Several months later, they often find themselves unemployed and frustrated.

According to Labour Force Surveys, there are around six million jobless youth in Pakistan. This is not just unemployment; it’s unemployment among university degree holders. The glaring lack of correlation between formal education and employment is evident.

In industries such as information technology, healthcare, energy, and construction, employers frequently advertise vacancies that remain unfilled due to a shortage of applicants with the required technical expertise. Meanwhile, graduates with general degrees in arts or humanities chase after low-paying clerical jobs that are becoming increasingly scarce.

Economists call this dilemma Pakistan’s education paradox. The country produces degree holders faster than it creates meaningful jobs for them. This crisis is hurting the economy.

The Asian Development Bank estimates that the mismatch between education outcomes and market needs costs Pakistan about 2 to 3 percent of its GDP annually. This amounts to billions of dollars lost because young people are not trained in the right skills.

Agriculture is a striking example. Pakistan spent $10 billion on food imports in 2023-24 because farm productivity remains low. There are simply not enough trained agricultural technologists and irrigation experts to modernize the sector.

The ongoing energy crisis also stems from a shortage of renewable energy technicians and engineers. In healthcare, Pakistan’s weaknesses were painfully highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The country has fewer than one nurse per 1,000 people, while the World Health Organization recommends at least three. These shortages can be prevented through better vocational training planning.

Comparisons with some neighboring countries are stark. India’s IT industry exported services worth over $250 billion in 2023; Pakistan managed only $3.8 billion. Bangladesh, by focusing on training women in the garment sector, has taken its exports beyond $40 billion. Pakistan, however, has been unable to achieve similar growth.

Less than 20 percent of women in Pakistan are enrolled in technical or vocational programs. The World Bank reports that if women participated equally in the workforce, Pakistan’s GDP could grow by 30 percent.

The country’s main problem is not a lack of talent but a lack of direction. Schools and universities still prioritize rote learning. Students are rewarded for memorizing textbooks, not for solving problems. Universities rarely track how many of their graduates find relevant employment.

Although technical and vocational training institutes exist, their combined capacity—around 314,000 seats annually—is far below demand. Millions of young people are left with no option but to pursue traditional degrees that often lead nowhere. Those who opt for vocational diplomas or global certifications such as Cisco, AWS, or NEBOSH often earn more than graduates with master’s degrees.

To end this crisis, reforms must begin now.

School curricula need to change to introduce digital literacy, critical thinking, and practical training from an early stage. Strong connections between universities and industries must be made mandatory so students gain real workplace experience through internships and apprenticeships.

Technical education should be treated as equal to higher education, not as a lower-tier option. Government subsidies for international certifications can make it easier for young people to qualify for well-paid jobs both domestically and abroad.

Most importantly, women must be included in skill-building programs. To achieve this, safe training centers, childcare support, and digital opportunities must be expanded.

With 64 percent of its population under the age of 30, Pakistan is sitting on a demographic goldmine. This young population can be trained to drive the economy forward. Otherwise, it risks becoming a burden.

A degree without employable training is no more than a piece of paper. The future belongs to those who can design, build, repair, innovate, and deliver—not to those who simply recite textbooks.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/1345071-educated-and-unemployed