In September 1994, a pair of Swiss astronomers at a small observatory nestled in the south of France began training their telescopes on a star about 50 light-years from Earth, marking the beginning of the field of exoplanet research. The duo, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, had finally found something they’d spent 18 months searching for: a planet orbiting a star similar to our own.

This discovery was the first step toward a much more ambitious goal — to prove that we are not alone in the universe. Carl Sagan and other astronomers had already begun searching for intelligent life as early as the 1960s, but many of those efforts focused on detecting radio signals or other deliberate communications from intelligent, technological life-forms.

By the 1980s, astronomers realized they could also find potentially habitable planets by analyzing the light from their companion stars. Although astronomers had found hints of a planet orbiting a pulsar—an ultradense, magnetized star that beams radiation like a lighthouse—the extreme, destructive conditions around a pulsar made it highly unlikely that life could exist there.

Back in 1987, a Canadian team of astronomers thought they had spotted a planet around another star, but five years later, they concluded the signal did not indicate a planet. (Their initial hypothesis was ultimately confirmed in 2003.)

Meanwhile, Queloz and Mayor, who were working at the Geneva Observatory at the time, began looking for anomalies in the trajectories of nearly 150 smaller, more ordinary stars. They zeroed in on one such star: 51 Pegasi, located about 50 light-years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus.

This middle-aged, main-sequence star resembled our sun, and the wobble in its velocity suggested it was being tugged back and forth by an orbiting planet. Analyzing the star’s light revealed the presence of the planet, which scientists named 51 Pegasi b, or Dimidium.

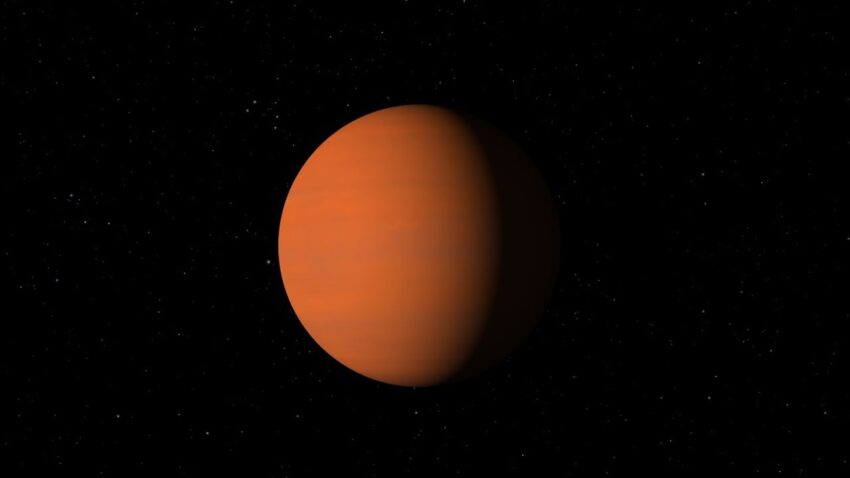

The astronomers discovered that the planet was likely a “hot Jupiter” — a giant gas planet that orbits very close to its star. Dimidium is a gas giant larger in diameter than Jupiter but with about half its mass. It orbits just 5 million miles (8 million kilometers) from its star, completing a revolution every 4.2 days.

Soon after, scientists at the Lick Observatory in California confirmed the discovery. On November 1, 1995, Queloz and Mayor published their findings in the journal *Nature*, opening the floodgates to exoplanet discovery.

Following this breakthrough, dozens of exoplanets were found, sparking a race to search for planets that could harbor life and leading to the development of new discovery techniques. In 2004, astronomers using the Very Large Telescope in Chile captured the first photographic evidence of an exoplanet orbiting a distant star, with hundreds more soon to follow.

In 2019, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their groundbreaking work on Dimidium, sharing the prize with Canadian physicist James Peebles, who contributed to our understanding of dark energy and dark matter in the universe.

https://www.livescience.com/space/exoplanets/science-history-astronomers-spot-first-known-planet-around-a-sunlike-star-raising-hopes-for-extraterrestrial-life-nov-1-1995