The icon indicates free access to the linked research on JSTOR.

The Tunnels of Moose Jaw is one of the major attractions in Saskatchewan’s fourth largest city. This below-ground theme park, as historian Ashleigh Androsoff explains, offers tours that claim to tell two local stories: one about Chinese immigration circa 1905, and the other about Chicago-style gangsters circa 1929.

According to the Tunnels’ narrative, Chinese immigrants built a network of tunnels under the city because they were forced to live underground. These tunnels were then supposedly used by gangsters and bootleggers, including the infamous Al Capone. Capone’s rumored presence — though town historians have found no evidence he was ever in Moose Jaw, above or below ground — sparked a change in the city’s slogans in 2019. The “Surprisingly Unexpected” and “Friendly City” became known as “Canada’s Most Notorious City.”

In reality, as Androsoff argues, little of that story is supported by historical evidence. One of “Canada’s ‘Coolest Downtowns’” is, to some extent, a bit of make-believe. As the local paper once noted, “it’s good business to tell tales to tourists.”

“If ‘history’ is understood to mean a plausible narrative of the past based on sufficient, reliable, and compelling evidence, there is little about the Tunnels of Moose Jaw that is ‘historical,’” Androsoff writes. The presentation of “history” at the Tunnels is riddled with misleading and inaccurate information.

This is unfortunate because the real historical significance of Moose Jaw tells a very different story. Contrary to popular myth, Moose Jaw was actually unusual for its welcoming stance toward Chinese immigrants — a notable achievement given the often violently racist reactions to Asian immigrants in North America at the time.

Meanwhile, the city’s railroad connections and tolerant attitude made it a regional hub of vice during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, all the drinking, gambling, and prostitution occurred above ground and out in the open. Local police “preferred management and containment over suppression” and were likely taking a cut from these “profits-of-sin.” Even during provincial Prohibition (1915–1925), Moose Jaw remained a remarkably peaceful and orderly city — a far cry from the “Little Chicago” image promoted by the Tunnels.

Androsoff uses the “physical and discursive construction” of this underground space to explore “the processes of community building, economic recovery, and urban redevelopment in a deindustrializing city over time.”

The theme park was developed by the city’s entrepreneurial and political elite to help Moose Jaw recover from the agricultural and industrial busts of the 1980s and 1990s. Business leaders and boosters — if not the public library’s archivist — believed that rumors, legends, and the city’s network of sub-cellars, basements, coal chutes, and other subterranean utility spaces made for a marketable tourism product. The image of American-style gangsters, or at least the cartoonish, movie-influenced version of them, proved to be a real draw.

The attraction originally opened as the “Tunnels of Little Chicago” in 1996 and was rebranded as the Tunnels of Moose Jaw in 2000. According to Androsoff, the Tunnels have helped boost the city’s economy and reputation — but at a cost. Visitors (based on online reviews and other comments) and locals alike often take the entertainment as historical truth.

This “fantasy packaged as history and heritage,” to quote a historical geographer cited by Androsoff, is becoming the dominant local story. “Instead of seeing Moose Jaw for the fascinating, tolerant, and ‘wide-open’ place it really was,” she writes, “the city — led by Tunnels supporters — has buried itself in the false narrative of being a ‘Little Chicago’: something other, and less than, itself.”

“Moose Jaw’s vice market and experience of prohibition were not the same as Chicago’s, and it’s worth understanding how and why they differed,” Androsoff emphasizes.

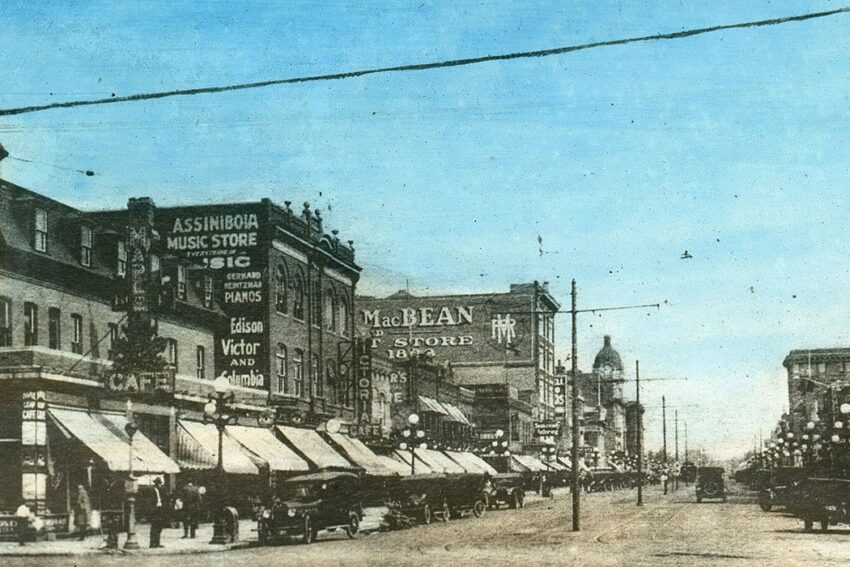

The primacy of “heritage” commodification over actual history reveals a bittersweet irony in Moose Jaw. The city’s Main Street is one of Canada’s best preserved historic streets, yet there are no remaining traces of the once-rollicking River Street — Moose Jaw’s actual above-ground red-light district, once famed even south of the 49th parallel.

https://daily.jstor.org/under-moose-jaw-tourism-or-history/