Julian Fleisher remembers fondly the first time he ventured inside the St. Marks Place establishment Boy Bar one fateful night in 1991, with the intention of having a “good old gay time.” Then in his early 20s, the aesthetically unremarkable East Village spot promised him the opportunity to have some fun and meet other men. Little did he know, it would also be his entry point into the magical, unruly world of downtown drag.

There, standing before him, was the great Mona Foot, a rising star in the East Village drag scene, lip syncing to Sweet Pussy Pauline. When her performance concluded, Fleisher threw himself at her, starstruck “like a school girl, like a crazy fan.”

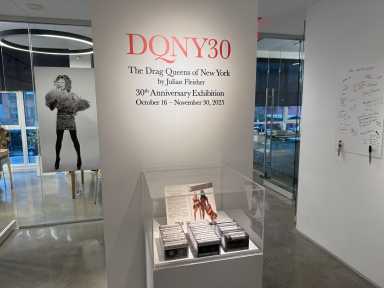

“She doesn’t simply mouth the words, she rides a song like a cowboy rides a bronco,” Fleisher would later write of Mona Foot, known out of drag as Nashom Wooden, in his groundbreaking book *The Drag Queens of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide*, published by Riverhead five years later in 1996. “She penetrates it, bends it to her will.”

Mona, who appeared in the 1999 movie *Flawless*, tragically died of COVID-19 in 2020.

Long before the days of *RuPaul’s Drag Race*, the East Village drag scene of the mid-90s centered around queer nightlife venues like The Pyramid Club and Boy Bar. These spots were not glamorous—they were raw, gritty, and full of character. Fleisher remembers the Pyramid Club of the ’90s as a nondescript “big old wooden bar.” Through its doors was a room for dancing, with a small stage and a basic lighting system, reminiscent of an “adult version of a summer camp theater—kind of raw and dumpy.” Boy Bar had a downstairs lounge for cruising, with no bright colors or sequins on display.

Yet it was the mundane appearance of these spaces that made their spotlights shine all the brighter. “It was the people that turned them into magic,” Fleisher said. “The DIY-ness of it is part of why it was fun.”

Linda Simpson, one of the many talented drag queens featured in Fleisher’s book, described the seven-year period from the late 1980s to the mid-90s as a time when drag began evolving into a “mainstream sensation.”

“There was a certain sensibility that reigned: campy, goofy and bohemian,” Simpson told *Gay City News*. At a time when many articles sensationalized drag queens, Fleisher’s writing was “more respectful, got the humor, got the insights,” she said.

Simpson first stepped into these spaces as an observer, watching legends like Lady Bunny, Happy Face, and Taboo!. Soon after, she ventured into drag herself, stepping into the Pyramid’s dressing room—a hotspot for socializing. Most queens lived downtown, forming a close-knit community in and out of the clubs. Many were also employed as gogo dancers, making it common to see “a wall of drag queens on the bar shaking their stuff.”

Simpson has played an important role in preserving drag history herself, publishing nightlife images in her recent book *The Drag Explosion*. Her 1980s-90s zine *My Comrade* featured “rough-hewn stories of urban gay life and poorly reproduced, unretouched centerfolds of fleshy East Village boys in well-worn underpants,” Fleisher wrote, along with “camp variations on a glam-rock theme and profiles of still-unknown drag queens.”

What made that time so special to Fleisher—especially in an age before the internet—was the ephemerality of it all. “Their lunacy was bespoke. It happened in that room on that night for that audience, and that was it,” he explained. “And that feeling that this is for nobody else but us is a very special feeling.”

“It was unmoored and untamed,” he recalls. Not least because, unlike today’s drag institutions, “there was no panel of judges.” The goal was not to compete for wealth, power, or success—but to critique those very concepts.

This all took place during the height of the AIDS crisis, a period when the LGBTQ community was persevering through tremendous loss and adversity. Looking back on his own writing, Fleisher realizes that while it wasn’t often explicitly discussed, the crisis was inescapably present—almost as if drag were “the entertainment portion of the AIDS crisis.”

“There was a need for escapism, so people partied a lot because there was this doom and gloom all the time,” Simpson added.

Through his book, Fleisher’s goal was to create a portal between the drag world and the “real” world. He imagined his ideal reader as “some straight dude” walking through the East Village, holding a subway map, a cup of coffee, and a field guide.

There were moments when those worlds collided—for example, when Fleisher received a three-page-long lawyer’s letter before publication. The letter asked him to justify claims that, to Fleisher and the queer New York scene, were facts but appeared legally questionable. These included confirming that The Anvil was a sex club, referencing Joey Arias “fellating the microphone in the middle of the act,” and other details some might find scandalous.

“East Village drag in the ’90s, with all of its grit and its weird, poorly lit, drug-addled, sleazy goodness—it was hard not to love it,” Fleisher reflected.

https://gaycitynews.com/exhibit-east-village-drag-history-new-york-city/